|

Back to Introduction

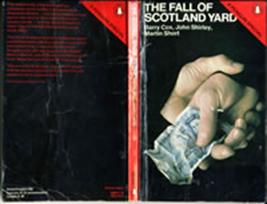

The Fall of Scotland Yard

by Barry Cox, John Shirley, Martin

Short

Penguin Books 1977

Chapter One

The Times Inquiry

‘Like catching the Archbishop of Canterbury in

bed with a prostitute,’ observed a leading criminal lawyer on breakfasting

with The Times on Saturday, 29 November 1969. Regular readers of this

prestigious newspaper could have been excused for thinking that it had been

taken over by a team from the Sunday People or the News of the

World, or that they were looking at the wrong paper on the wrong day.

Few could believe that The Times had sunk to such depths - or risen

to such heights - of reporting, for sharing the front page with speculation

about a 4½ per cent limit on wage increases and a picture of some

astronaut's footprints on the Moon was a robust piece of investigative

journalism, written with nerve, irreverence and initiative, qualities more

characteristic of the other end of the newspaper market. It was headed:

‘London policemen in bribe allegations. Tapes reveal planted evidence.’

The story, by Garry Lloyd and Julian Mounter,

went on to detail a series of meetings between a small-time professional

criminal and three seasoned detectives. The account is its own best

historian:

‘Disturbing evidence of bribery and corruption

among certain London detectives was handed by The Times to Scotland Yard

last night. We have, we believe, proved that at least three detectives are

taking large sums of money in exchange for dropping charges, for being

lenient with evidence offered in court, and for allowing a criminal to work

unhindered.

Our investigations into the activities of these

three men convince us that their cases are not isolated. We cannot prove

that other officers are guilty but we believe that there is enough suspicion

to justify a full inquiry.

The possible scope of corruption is disclosed by

the admission of a detective sergeant who has taken £150. The total haul of

this detective, Sgt John Symonds of Camberwell, and two others, Detective

Inspector Bernard Robson of Scotland Yard’s C9 Division, and Detective

Sergeant Gordon Harris, a regional crime squad officer on detachment from

Brighton to Scotland Yard, was more than £400 in the past month from one man

alone.’

The story explained that Robson had tricked one

‘Michael Smith’ (the pseudonym used throughout the article) into leaving his

fingerprints on a piece of gelignite, in order to blackmail him into

divulging the name of a receiver. When Smith hesitated to do this Robson

appeared to be only too willing to take £200 instead, through Detective

Sergeant Harris as his negotiator. Harris and Robson also suggested to Smith

that he ‘plant stolen cigarettes in a sweet shop belonging to one of his

enemies.’ The officers ‘would then raid the shop and either obtain money

from the receiver (sharing it with Mr Smith) or prosecute the man’. He did

not have to be a genuine receiver of stolen goods, as far as Robson was

concerned, for the detective was quoted as having said, ‘Then we’ll go in

and if it’s a good load he’s taken, then he can bloody well pay up and we’ll

give you fair shares ...’

Smith soon found the Yard men’s greed insatiable.

A fortnight after they had taken the £200,

‘Inspector Robson was feeling the need for further

funds. He summoned Mr Smith to a clandestine meeting in the Army and Navy

Stores at Victoria, a stone’s throw from Scotland Yard. Pacing past sales

counters and riding up and down escalators the inspector, Smith said

afterwards, told him of new plans to plant allegedly stolen property on him

and two of his associates.

The inspector, Mr Smith declared, informed him that

his department was mounting a weekend raid on Peckham SE, and medallions

which they would claim had been stolen from a shop that had been entered

near the Yard, would be ‘found’ in their possession.’

Robson then demanded £50 each from Smith and his

two colleagues for this information.

There were further alarming aspects to the story,

notably the implication that a number of other officers were up to the same

thing. But what gave the account an authenticity and a seriousness which was

later to compel the authorities to take it more seriously than other

journalistic forays into this murky area was the nature of the evidence. For

a month the Times reporters had not only watched and photographed

meetings between the criminal and the detectives, they had also immortalized

their incriminating conversations by means of concealed microphones and

recorders. The Times tapes transformed fairly routine allegations-of

police misconduct from a convicted criminal - the sort which are usually

thrown out of court without a hearing - into apparently irrefutable charges

whose authenticity was backed by acceptable witnesses: the two reporters, a

sound recordist and a Times photographer.

The tapes had the additional advantage of spicing

the story, as The Times itself observed, with the ‘cosy lingua franca

of the crime business, littered with picturesque but unprintable adjectives.

But they also gave the account its most sinister element. Detective Sergeant

Symonds was taking money from Smith independently. He appeared to have

nothing to do with the Yard men, but he seemed to know their kind. He

advised caution in regard to Robson, whom he guessed might be intending to

fit Smith up. ‘Because, what he is doing he might be trying to bleed you. He

might think, you know, well I’m on to a good one here … Because we’ve got

more villains in our game than you’ve got in yours, you know.’ ‘You’ve got

to watch all this because otherwise you will be — skint all your life.’

Robson would either give Smith a tip-off and ‘con dough out of you’ or ‘he’s

going to try and blag you for some money because Christmas is coming’.

Symonds’s own relationship with Smith was not

quite so predatory as that of his Yard rivals. There was no blackmail

involved, just payment for assistance rendered: £150 for getting Smith off a

possible charge of theft. Indeed, his relationship with Smith was avuncular:

a Camberwell Machiavelli advising his young Prince of Peckham on how he

should go about a successful life of crime. They could go into partnership.

While Smith was on a job Symonds would arrange distractions, false alarms,

raids on other premises, to clear the streets of patrolling bobbies. ‘If

it’s a big one I’ll come with you … you can’t have any better insurance than

that, can you?’ If anything went wrong they should have a ‘mug’on hand to

arrest instead, ‘then I’m a hero aren’t I? I get a - medal, or something.’

Symonds gave Smith advice on investment too. He

should put his profits into a little sweet shop with a bird running it.

‘Then if a wheel comes off [something goes wrong], so what? You’ve got a

home and a — business ...’

Symonds’s most important piece of advice was that

Smith should keep in touch with him so that he could arrange to look after

any case in which Smith was involved: ‘... don’t forget always to let me

know straight away if you need anything because I know people everywhere.

Because I’m in a little firm in a firm. Don’t matter where, anywhere in

London I can get on the phone to someone I know I can trust, that talks the

same as me. And if he’s not the right person that can do it, he’ll know the

person that can. All right?’ Through Symonds Smith could gain access to a

time-honoured system: ‘That’s the thing, and it can work - well it’s worked

for years, hasn’t it?’

In another taped conversation Symonds gave Smith

a related warning about the honesty of policemen outside the Metropolitan

force. ‘If you are nicked anywhere in London ... I can get on the blower to

someone in my firm who will know someone somewhere who can get something

done. But out in the sticks they are all country coppers aren’t they? All

old — swedes and that.’ To Symonds, it seems, ‘country coppers’ were either

naive or stupid, and their incorruptibility proved one or the other.

‘A little firm in a firm’ was taken as the

headline for the Times first leader that morning. Though Symonds may

have been exaggerating, his remarks were what gave the story its massive

dimensions. Without them the newspaper had published a very sound report of

serious police corruption. There appeared to be proof that three detectives

were prepared to plant evidence, commit perjury to obtain a false

conviction, take money in return for showing favours and urge a criminal to

act as an agent provocateur. As the Times leader stated, these

allegations constituted ‘the most serious charge that has been brought

against the Criminal Investigation Branch of the Metropolitan Police for

some years’. But it was the ‘firm in a firm’ conversations which gave the

account its horrific stature. They implied that there may have been a whole

seam of ‘bent’ coppers on the take, who were prepared to do just these sorts

of favours to anyone who could be induced to pay for them. With typical but

on this occasion justified Times solemnity, the leader ended, ‘it is

important in justice to the Metropolitan Police, and in particular to the

plain-clothes branch, that the most stringent inquiry should now be made.’

The inquiry demanded by The Times would

indeed be carried out.But the way it was to be handled, the time it would

take and its ultimate consequences were to be such that no one genuinely

concerned with discovering the truth of the newspaper’s allegations can,

even today, be remotely satisfied. Far from being ‘most stringent’, the

Metropolitan Police inquiry into the Times allegations was

effectively a cover-up job. It was handled in the main by an undistinguished

and deeply suspect detective chief superintendent who, in 1977, was himself

to face corruption charges at the Old Bailey of a scale which towered over

the petty achievements of Robson, Harris and Symonds. Even as he probed the

‘firm in a firm’, that investigator, Detective Chief Superintendent Bill

Moody, was corruptly taking vast sums of money in his other capacity as head

of the Obscene Publications Squad. How he was able to do this and yet still

be esteemed impeccable enough by his superiors to take on an inquiry of this

magnitude remains today a matter of mystery and deep concern.

On 3 March 1972 Robson and Harris were sent to

prison for seven and six years respectively. However, the loose-tongued

braggart Symonds had disappeared only a few days before that verdict, just

six weeks before his own, separate trial. He has never been seen in England

since. Of another two officers described but not named in the Times

article, neither was prosecuted but one was demoted. They were to remain in

the Metropolitan Police, though one has since resigned. Of the dozens of

officers investigated as a result of the Times allegations only

Robson and Harris went to prison.

Yet, even in 1972 - long before the truth about

Bill Moody came out in public - it was surprising that there were so few

prosecutions arising out of the Times allegations, especially to the

many senior provincial police officers who were convinced that Symonds’s

boast of a network of corrupt Metropolitan detectives was true. But such

‘outsiders’ were already aware that the police inquiry had been handled,

deliberately or through negligence, in such a way that the cork appeared to

have been thrust firmly back into the bottle. To the public it might have

seemed that Scotland Yard had sternly and without favour cleaned up its own

dirt, and also that there was not much dirt about. But behind the simplicity

of some newspaper allegations in 1969 and their confirmation at the Old

Bailey some two and a half years later is a story of bitterness,

incompetence and undeclared war between men whose unanimity, cohesiveness

and mutual trust were essential, both for cleaning out corruption inside the

Metropolitan Police and for an effective fight against crime throughout

England and Wales. The Times report precipitated a series of bitter

feuds, both inside Scotland Yard and between Yard chiefs and those

provincial officers who were appointed to ‘advise’ on the inquiry’s conduct.

At the Home Office, those civil servants with responsibility for the

Metropolitan Police, who had known in general terms about the existence of a

criminal element within the force for some years, at last felt able to take

some public action. An influential section of the public had been made aware

that there was corruption and that it might be widespread. It is no

exaggeration to say that the way the Times revelations were treated

by the Met clinched Robert Mark’s succession to the job of Commissioner.

Many of his reforms were both made possible and shown to be essential

because it had become clear that the will and capacity of the Met to

investigate allegations of corruption made against itself were very limited

indeed.

The Met had to be straightened out, in order to

end the incapacitating mutual distrust of Scotland Yard detectives and their

provincial counterparts, to establish an effective internal method of

investigating corruption and to lay out a code of conduct for detectives in

their relationships with criminals. The intimate bonds so often built up

between London’s plainclothes men and the underworld had been shown to be so

dovetailed with mutual obligations that it had become almost impossible for

all but the most resilient of detectives to avoid being compromised. The

role of the informant, also, so often degenerated into the illegal one of

agent provocateur, the instigator of crime. And in some convoluted

relationships the CID man brought greater benefit to himself as a supplier

of information to criminals, to ease their own success and enable them to

evade detection, than as someone for whom informants were to be cultivated

only in order to solve and prevent crime. To that extent, Robson, Harris and

Symonds were themselves the victims of a system which put massive temptation

in their way as a matter of course. They did not resist it. How many of

their colleagues were equally irresolute? The Times inquiry itself

conspicuously failed to answer this question. But the way in which it was

mishandled gives some indication that Sergeant Symonds spoke very near the

truth on the Times tapes. ‘The firm in a firm’ was a big and thriving

concern.

There had been no thought of police corruption,

of tapes or trials, in the mind of the bright spark at The Times in

1968 who placed an advertisement - in another newspaper naturally - for a

former burglar to help with a series of articles on how to protect houses

from theft. Among the applicants was a certain Mr Eddie Brennnan, burglar

(retd). As Garry Lloyd said at the trial of Robson and Harris, ‘The Times

were contemplating renting a house for Brennan to break into to show how

easy it was, to advise people how to protect their goods. We were concerned

at the number of antiques being stolen’ (an affliction suffered, it seems,

by many readers of The Times). ‘The object of the exercise was 'to

stock the house with antiques. We would watch it burgled so that we could

describe it in the series. We decided that it was much too ambitious,

expensive and risky a project. ‘So then they decided to write an article

merely with Mr Brennan’s advice. It was partly this totally fortuitous entry

into the minefield of investigating corrupt policemen that was to give the

Times reporters their indestructibly honourable air in court. For,

far from seeking an anti-police story, they had it thrust into their hands

one year after the burglary article, when Brennan got in touch with The

Times to introduce a distressed young friend who was in need of advice.

This was one Michael Roy Perry, a car dealer aged twenty-two, who was to

become the Michael Smith of the original Times reports. Perry had a

string of criminal convictions and was on the way to getting a couple more.

On 27 October 1969 Perry went to The Times because he felt himself to

be in danger not just of having to pay sums of money to bent detectives -

this he seemed to accept as part of his professional dues - but of being

sent down on framed evidence for an offence which was punishable with many

years’ imprisonment. His alternative, an unattractive one bearing in mind

the company he kept, was to turn informer on receivers of stolen goods.

Perry was also concerned about being nibbled at more than one end, by some

greedy Scotland Yard men at the same time as by his friendly neighbourhood

sergeant.

Perry had first met Robson and Harris only a few

days before, on 21 October, when they were among officers who were raiding

the Peckham flat which he shared with Robert Laming. The detectives found

twelve bottles of whisky and also some plasticine, sticking plaster, a

battery and some wire. At this point Robson apparently said to Perry, ‘a bit

of gelly would go nice with this and I know a man who can get some’. This

remark seemed to indicate to Perry that Robson was prepared to fit him up

with the one ingredient missing for a small safe-blowing kit. Perry laughed

and pointed out that he had merely been dismantling a transistor radio, but

Robson told him not to laugh as he was serious. Unless Robson was told the

whereabouts of two men called Brooks and Kelly, he would get some gelignite

and arrest Perry for possession.

Perry was already in enough trouble, for he was

later charged with dishonestly handling the whisky, knowing it to be stolen.

He was kept in custody and appeared the following day at Tower Bridge

Magistrates Court, pleaded guilty and was fined £40. While he was in his

cell, waiting to appear, Harris visited him and said, ‘we will get it over

today but you will have to give the big bloke a drink’ - the ‘big bloke’

meaning Robson and ‘a drink’ meaning a bribe. Perry took the hint and

promptly agreed to pay £25. In return, Harris did not mention, when he

testified in court, that Perry already had a similar conviction. In fact

Harris should not have mentioned it anyway, since it was a juvenile offence.

Nevertheless, Perry believed that Harris had done him a favour. The same day

Perry went straight to some friends, the Laming brothers James and Robert,

borrowed the money and met Harris at The Edinburgh Castle in Nunhead Lane,

Peckham - the faded inner London suburb in which most of these transactions

were carried out. In an alley outside the pub Perry paid Harris the £25 and

asked whether that was the end of it or whether they would still be on his

back. Harris answered, ‘No, you’re in the clear. If you get into any trouble

give me a ring’ - on his extension at Scotland Yard.

A few days later, on the 25 October, Perry was in

a car with Robert Laming and a man called O’Keefe when they visited the home

of James Laming. They arrived to find two car-loads of police officers,

including Robson, waiting to talk to Robert Laming. With immediate presence

of mind Laming leapt out of the car, ran straight through the house, jumped

over the back wall and was away. Perry and O’Keefe stayed in the vehicle.

Robson came up and said to Perry, ‘Let’s have a look at your hand.’ Perry

held out his left hand, Robson put his arm through the car window and

‘pressed a sausage-shaped thing in grease-proof paper on my fingers with the

words “there is the gelly I promised you”.’ Robson took back the substance

and put it in his pocket. ‘Unless I gave him the name of the receiver he

would put it into the Yard so they would find my fingerprints on it.’ Robson

added ‘I do not like doing this but unless you give me the names of the

receivers the gelly is going in.’ Perry asked to have the weekend to think

it over and agreed to meet Robson in The Grove Tavern in Dulwich the

following Monday.

By this time Perry was really scared. He decided

to get in touch with a solicitor, but it was a Saturday afternoon and all

solicitors’ offices were closed. Then he happened to meet his friend Eddie

Brennan who suggested a meeting with The Times. He called his contact

there and a memo about the conversation landed on Garry Lloyd’s desk. Lloyd

decided that the tale was worth an hour or two’s effort. On the Monday he

went to The Grove and observed Perry’s meeting with Robson, but he was

unable to hear the conversation properly. Lloyd then took Perry back to

The Times to make a statement, and it was at this point that the full

dimension of the story became clear. Perry was not claiming that he was an

isolated victim. Many petty criminals of South London had similar

relationships with detectives, particularly Detective Sergeant Symonds and

another more senior local detective. Lloyd was told that licences to commit

crime, without fear of arrest, had become a regular feature of the Peckham

and Camberwell area. The payment of bribes was accepted, more or less

willingly, as part of the price of being a criminal, in much the same way as

law-abiding citizens grudgingly pay their taxes. However, fitting up and

blackmailing these small-timers was another matter, as Symonds had

immediately recognized.

Perry’s statement convinced the Home News Editor,

Colin Webb, that the allegations it contained had to be proved or disproved.

There was no leaving it aside as the disgruntled imaginings of a convicted

criminal, however implausible a witness he would appear if ever these

matters were to be brought before a jury. Of course, Perry was highly

implausible. His previous convictions stretched back to his childhood and

included occasioning actual bodily harm, aiding an escape from a remand

centre, loitering with intent, stealing a car radio and causing malicious

damage to a police motor cycle. He was fresh from the whisky offence and he

had yet another charge hanging over him, for stealing a van and its

contents.

Garry Lloyd and Julian Mounter, who had joined

the investigation just two days after it started, were extremely suspicious

of Perry. If they were going to get deeply involved in testing his

allegations, how could they be sure he would not renegue and simply drop the

whole story? They decided to ‘put him through the hoop’, repeatedly

cross-questioning him on his statement. But they soon appreciated that the

only type of people who got mixed up in this sort of thing were, almost

inevitably, convicted criminals whose words no jury ever wanted to believe.

And words were all the evidence there was likely to be. ‘Bent’ policemen

don’t give receipts. Perry for all his incriminated past was the cleanest of

a bunch of petty criminals the reporters were to interview and they had the

feeling he might be telling the truth.

Yet there would still have to be some neutral

form of testimony to verify what Perry was alleging. The very nature of the

transactions meant that no outsider could ever be present, only the donor

and the recipient. No reporter, however intrepid, could reasonably expect to

overhear such dealings, and, if he did, why should he be believed rather

than a police officer? The Times therefore decided that an attempt

should be made to record conversations between Perry and the detectives. A

sound engineer, Ernest Hawkey, was added to the investigative team and also

a staff photographer, Warren Harrison.

The first recording was made on 30 October at the

Woolwich home of Perry’s mother. It lasted two to three minutes and

consisted of a pre-arranged phone call to Sergeant Harris at Scotland Yard.

During the call Perry offered to pay Harris another £25, to get off the

gelignite charge, rather than name a receiver. There still had to be some

negotiations, so they agreed to talk it over that evening at The Edinburgh

in Peckham. For this encounter the Times team arranged two methods of

recording: a sensitive microphone was fixed under the dashboard in Perry’s

car and connected by a wire running under the car to a recorder in the boot.

A second microphone was placed inside Perry’s shirt and was wired to a

transmitter in his overcoat pocket, which was in turn tuned to a tape

recorder in a van to be parked near by.

Perry drove to The Edinburgh and switched on the

tape recorder. Harris climbed into Perry’s car and a first-rate recording

resulted, but only from the dashboard mike. The radio mike was not

successful, as the batteries ran down after four or five minutes. On the

recording Perry and Harris discussed the amount of money needed to get Perry

off the gelignite charge. A minimum of £100 was agreed and arrangements were

made for a meeting with Robson the following day, 31 October.

This proved to be the first of three meetings

about the gelignite, during which a total of £200 changed hands. Immediately

before the first transaction the Times reporters searched Perry to

check the amount of money he was carrying - £55 - and took down the numbers

of the notes. But they were unable to record the conversation. Perry got out

of his own car and into the detectives’ vehicle, which was parked out of

range of the radio recorder. However, Harrison, the Times

photographer, managed to take a few shots. While Perry was with the

detectives they noticed the sound engineer and his assistant sitting in

another car. Robson and Harris asked Perry if he knew who they were. Perry

with astonishing presence of mind said he thought they were policemen, thus

ending the detectives’ curiosity.(1)

It was during this encounter, according to Perry, that Robson said it would

cost him a ‘twoer’, meaning £200. Perry said he only had £50 on him, which

he duly paid over. When Perry returned, the reporters searched him again and

found only £5.

For the second payment on 3 November it was

decided to apply more elaborate recording techniques. A mike was hidden on

Perry, linked to a recorder in the boot of his car. Perry was also wired up

with a portable cassette recorder, strapped on his back. On this occasion

Perry had £75, and again the numbers were noted. Perry drove to the

rendezvous, The Grove in East Dulwich, and switched on the tape recorder in

the boot. But again the attempt failed. The entire recording consisted of

‘Good morning. No aggravation?’ from Harris, ‘not really’ from Perry, six

minutes of silence and then ‘see you later’. During that silence Perry had

got into the detectives’ car, a sturdily built Volvo with too thick a body

for the radio link to penetrate. As for the cassette, Perry could not start

it. However, he did manage to pay over the £75, which he was told to push

down the back seat. Perry later claimed that they had talked of ‘setting up’

a receiver, and that they discussed the possibility of using the tobacconist

under Perry’s flat, a man called Skipton, who was also Perry’s landlord.

Robson suggested that Perry should take some stolen cigarettes into the

shop, which the police would then raid. Skipton would either pay up or be

prosecuted. On Perry’s return the reporters found no money on him.

The next meeting was arranged for 5 November,

again in the car park of The Grove Tavern. Perry was to pass a further £75

to complete payment of his gelignite debt. The disastrous experience of the

Times team now drove them to using four recorders, turning Perry into

a portable transmitting station. This time three recorders worked and most

of the subsequent conversation was recorded on one or more of the machines.

Again, the meeting was photographed by Harrison.

On these recordings it is quite clear what was

going on. ‘I don’t — play games. When I stuck that in your hand that’s there

for keeps ... I was going to stitch you.’ Referring to one of the earlier

meetings Robson made it clear that he was ready to commit perjury: ‘I told

you in the car that with that gelly I would stand there, and believe you me

you could say what you liked and it would make no -- difference so don’t

think you’ve wasted your money. You’ve got off well because you haven’t put

up a buyer, which is what I really wanted.’ Perry had for the time being at

least fulfilled his obligations. ‘Now you’ve paid your £200 we’re quits.’ He

had his anxieties about the future, but was reassured by Robson: ‘What do

you think we are, professional blackmailers?’

Again, the issue of planting the tobacconist was

brought up by Robson. He was anxious to further his investigations into the

activities of a skeleton key gang and needed to produce a receiver. But

Robson seemed uninterested in whether that ‘receiver’ was guilty or

innocent. He encouraged Perry to sacrifice anyone who might be bothering

him. ‘If there’s anybody that’s ever done you a mischief ... that wants

seeing to, you see what I mean? ...’ Perry suggested somebody, but he wasn’t

sure whether that person was still working. Robson was undismayed: ‘Oh,

we’ll do him again.’ The victim, whoever he was, would either pay up - and

Perry would share the profits with the detectives - or he would be

prosecuted.

But Robson was not as good as his word. His

assurance to Perry that the gelignite affair was now closed was overtaken

two weeks later when Perry received a message that Robson wanted to speak to

him. Perry tipped off The Times again, and they recorded his call to

Robson. Perry was worried about the subsequent meeting, for he feared that

Robson must have heard about the tape recording. Luckily for Perry, Robson

was interested only in further donations and, during their encounter at the

Army and Navy Stores near Scotland Yard, a bizarre and blasphemous

conversation was recorded, albeit garbled and obscure. Talk of ‘all those

bloody crucifixes’ concealed the tip-off that Perry and the Laming brothers

were to be raided and fitted up with stolen medallions. For this favour

Robson required £50 from each of them.

The raid duly took place, early on Saturday, 22

November. Two of the trio were not at home. The third was taken to East

Dulwich police station but was released without being charged. The fit-up

scheme, if it had ever existed, had collapsed. The following Monday Perry

and Robson were to meet for the next payoff, once more at The Grove.

Again Perry was searched by the reporters before

and after the meeting, and again the conversation was recorded. Perry paid

his £50, but told Robson the distressing news that James Laming was refusing

to pay. Robert Laming would pay, but he simply did not have the money. The

inspector seems to have believed that he could make them pay. But this was

on a Monday, and by the following Saturday The Times had published

its revelations, so Robson never received the rest of his unofficial

Christmas bonus.

Throughout its investigations The Times

had acted with blanket secrecy. The Home News Editor, the reporters, the

recordist and the photographer, as well as Perry and his friends, had let

nobody know what they were up to, although, of course, the Editor of The

Times had been kept informed. Every night Garry Lloyd typed out the

notes he had been taking throughout the day, while Julian Mounter took

statements and had them signed. A separate file was kept on each specific

case or incident as it took place. The tapes too were immediately

transcribed, then locked away in a filing cabinet beyond anyone’s casual

attentions.

It was about this time that the newspaper men

decided on a crucial, and later fiercely criticized, tactic. The Times

chose to withhold its findings from the Metropolitan Commissioner until the

eve of publication, because of its fear that ‘'the whole matter could be

hushed up and might not have come to light at all’. As Garry Lloyd said in

the trial of Robson and Harris, ‘During our inquiry we had knowledge that we

were inquiring into “a firm within a firm”. When you are dealing with a firm

within a firm you do not know who is the managing director.’ It was

therefore thought unwise to consult the police. ‘We considered that it would

be most unsatisfactory to ask detectives or policemen to inquire into the

alleged misdeeds of their colleagues.’

After many editorial conferences it was decided

that the Lloyd/Mounter material would be published on Saturday, 29 November.

At 8 o’clock the previous evening Colin Webb, the Home News Editor,

telephoned the press office at New Scotland Yard and stated his intention to

publish serious allegations against senior detectives. It was suggested to

him that he call at New Scotland Yard with the evidence. At 10 p.m. Webb and

Mounter arrived and were directed to see Detective Inspector Kenneth Brett,

who was the Night Duty Officer for C1 Department, which dealt with

allegations of serious crime. Brett was handed two sealed parcels, a letter

addressed to the ‘Commissioner or Deputy’ and a copy of the first edition of

The Times. Brett read the articles, at once recognized their

seriousness and telephoned his superior, Detective Chief Superintendent

Collins of C1, at his home.

A hurried statement was issued by Scotland Yard,

acknowledging-receipt of the newspaper, tapes and documents, including

signed statements alleging bribery and corruption. ‘Notice has been taken of

this matter and an inquiry is in hand.’ Brett had also telephoned Peter

Brodie, who as Assistant Commissioner (Crime) was the Yard’s top detective.

It was decided that two chief superintendents should go through the Times

material, to be ready to brief Brodie at 10 a.m. on Saturday morning. The

men chosen were Roy Yorke, because he was the most senior chief

superintendent and acting Commander, and Fred Lambert, because he was ‘top

of the frame’, Yard jargon for Buggins’ turn, being on call at the time for

whatever happened to come up. Yorke’s part in the matter was to end after

the meeting with Brodie, but Lambert was to head the subsequent inquiry in

its early months, until he was removed in the most strange and

unsatisfactory circumstances.

Lambert opened the two sealed parcels in front of

Webb and Mounter. They contained statements from Lloyd and Perry, the tapes

and the tape transcripts. Overnight Lambert and Yorke read through the

evidence, but by the morning they were not the only policemen aware of the

contents. Before The Times was available from newsagents early that

Saturday, several of the five officers either named or anonymously described

in the newspaper were well aware of overnight developments. Indeed they

might have been capable of briefing Brodie themselves. By the time the

Assistant Commissioner (Crime) was meeting Lambert and Yorke, Robson was

already discussing the revelations with a colleague in C9 Department, the

Regional Crime Squad.

Detective Sergeant Symonds had been particularly

quick off the mark. Sometime around 2 a.m. he had made contact with Ronald

Williams, a convicted criminal, who was familiar with Symonds’ style of

policing - indeed he was later named in one of the charges brought against

Symonds. But at this early hour Symonds was trying to intimidate Williams

into saying nothing.

Symonds immediately went on the attack. On

Saturday morning he contacted Victor Lissack, a leading solicitor, and

summoned him down to his home in Orpington, in the north-west Kent suburbs

of London. After a miserable drive through typically rainy November weather,

Lissack arrived to find his new client, a robust and weighty man, laid low

with influenza. But he was well enough to protest his innocence and Lissack

soon issued a statement saying that Symonds repudiated emphatically all the

allegations, and that a writ for libel would be issued against The Times

and its reporters early in the coming week. Within a few days Robson and

Harris announced similar action.

The Metropolitan Commissioner, Sir John Waldron,

was equally concerned about the Times allegations. It was arranged

that he would receive a preliminary report from Detective Chief

Superintendent Lambert on the Monday, and then he would decide whether to

hold a further inquiry.

Waldron and his senior colleagues had been

devastated by what they had read in The Times. According to one of

the Yard’s most senior officers at the time, the Metropolitan hierarchy were

thunderstruck not so much by the allegations but by the sneaky and

ungentlemanly way the ‘evidence’ had been put together. If the newspaper had

developed such strong suspicions about the behaviour of London policemen,

why had not the Editor placed the preliminary evidence with the Commissioner

himself? The allegations would have been investigated without mercy and

followed through, if justified, into the criminal courts. The Times’

sensational method of revelation gave the suspects the most public notice

possible that they should get rid of whatever incriminating evidence they

might have had.

But the predominant feeling of top Yard men, no

longer conversant, if they ever had been, with the day-to-day methods of the

detectives who worked under them, was that of stubborn disbelief. How could

The Times rely on the word of a professional criminal and on tape

recordings which might easily have been forged or edited? Why did it entrust

such an important story to two young and inexperienced reporters? How could

the newspaper have proceeded with publication when it was bound to prejudice

the chances of fair trial? Worst of all, how could The Times of all

papers stoop to denigrating the reputation of Scotland Yard? There could be

no more offensive spectacle than one symbol of British integrity, respected

throughout the civilized world, attacking another, the world's greatest

police force.

Yet the truth was that Lloyd and Mounter, though

in their twenties were certainly not inexperienced. They had both been

reporters since they were sixteen, with local and regional papers, and Lloyd

had worked for the Press Association. They had each been with The Times

for four years.

Over the weekend of publication, politicians,

civil servants and editors of other newspapers urgently considered the Times

allegations and what should be done about them. Maurice Edelman, who was

both a Labour MP and a journalist, expressed the dismay which was common in

some circles: ‘I think it is wrong that The Times should have

denounced these police officers in a way which, had court proceedings

already begun, would have constituted a contempt of court, and I think

The Times was wrong because it used as a provocateur a convicted

criminal armed with a bugging device to seek to trap these detectives.’

The Sunday Mirror took a different view

and called for an independent inquiry, as did Lord Ted Willis, creator of

that plodding paragon of constabulary virtue, Dixon of Dock Green. In this

they were in accord with the 1961 Report of the Royal Commission on the

Police, which had recommended ‘that wherever practicable an

investigating officer, appointed to conduct a formal investigation under the

Police (Discipline) Regulations, be appointed from a division of the force

other than that in which the alleged offender is serving’. But in this case

did ‘division’ mean the immediate specialist detective division or a

geographical one? Or did it mean the Metropolitan CID? Or should it have

meant the entire Metropolitan police force?

The crucial dilemma now confronting the Home

Secretary was how to ensure that an investigation into the Times

allegations could be seen to be carried out properly when the law itself

effectively prevented this. Although there was some pressure to appoint an

‘independent’ inquiry, there was no legal authority for it to be conducted

by anyone other than a police officer. In that sense it could not be truly

independent. There was indeed no legal authority for appointing an

investigating officer from outside the Metropolitan force. According to the

1964 Police Act, when a complaint was made against a policeman the chief

officer of his force was to set up an investigation ‘and for that purpose

may, and shall if directed by the Secretary of State, request the chief

officer of police for any other police area to provide an officer of the

police for that area to carry out the investigation’. But the Metropolitan

Police was specifically exempt from this obligation. It had never yielded,

and had never been forced to yield, its total authority to investigate

complaints made against its own officers. As by far the biggest force in the

country, with an authorized establishment of over 26,000, the Met had been

left alone, on the grounds that it would always be possible to find an

investigating officer from within who did not know the alleged offender well

and who could be relied on to conduct the inquiry thoroughly, without favour

or malice. This the Royal Commission had recognized, for it said in a

footnote that its recommendation was already the practice in the

Metropolitan force.

(1)

October was also the day of the first recording with Symonds and again there

was an anxious moment. Symonds nervously jested, ‘You haven’t got this thing

bugged or something? ...’ Perry joked back, ‘Put a hanky over your mouth.’

It was during this conversation that Symonds made his ‘firm in a firm’

remarks.

Go to Part 2 |